What is the internet? 13 key questions answered

What is the internet?

The internet is the wider network that allows computer networks around the world run by companies, governments, universities and other organisations to talk to one another. The result is a mass of cables, computers, data centres, routers, servers, repeaters, satellites and wifi towers that allows digital information to travel around the world.

It is that infrastructure that lets you order the weekly shop, share your life on Facebook, stream Outcast on Netflix, email your aunt in Wollongong and search the web for the world’s tiniest cat.

How big is the internet?

One measure is the amount of information that courses through it: about five exabytes a day. That’s equivalent to 40,000 two-hour standard definition movies per second.

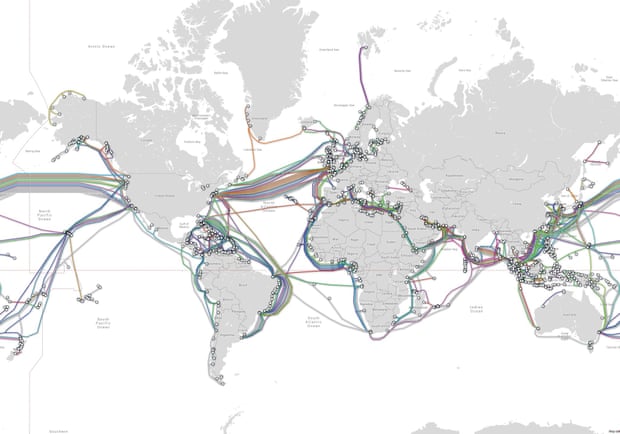

It takes some wiring up. Hundreds of thousands of miles of cables criss-cross countries, and more are laid along sea floors to connect islands and continents. About 300 submarine cables, the deep-sea variant only as thick as a garden hose, underpin the modern internet. Most are bundles of hair-thin fibre optics that carry data at the speed of light.

|

The cables range from the 80-mile Dublin to Anglesey connection to the 12,000-mile Asia-America Gateway, which links California to Singapore, Hong Kong and other places in Asia. Major cables serve a staggering number of people. In 2008, damage to two marine cables near the Egyptian port of Alexandria affected tens of millions of internet users in Africa, India, Pakistan and the Middle East.

Last year, the chief of the British defence staff, Sir Stuart Peach, warned that Russia could pose a threat to international commerce and the internet if it chose to destroy marine cables.

How much energy does the internet use?

The Chinese telecoms firm Huawei estimates that the information and communications technology (ICT) industry could use 20% of the world’s electricity and release more than 5% of the world’s carbon emissions by 2025. The study’s author, Anders Andrae, said the coming “tsunami of data” was to blame.

In 2016, the US government’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory estimated that American data centres – facilities where computers store, process and share information – might need 73bn kWh of energy in 2020. That’s the output of 10 Hinkley Point B nuclear power stations.

What is the world wide web?

The web is a way to view and share information over the internet. That information, be it text, music, photos or videos or whatever, is written on web pages served up by a web browser.

Google handles more than 40,000 searches per second, and has 60% of the global browser market through Chrome. There are nearly 2bn websites in existence but most are hardly visited. The top 0.1% of websites (roughly 5m) attract more than half of the world’s web traffic.

Among them are Google, YouTube, Facebook, the Chinese site Baidu, Instagram, Yahoo, Twitter, the Russian social network VK.com, Wikipedia, Amazon and a smattering of porn sites. The rise of apps means that for many people, being on the internet today is less about browsing the open web than getting more focused information: news, messages, weather forecasts, videos and the like.

What is the dark web?

A search of the web does not search all of it. Google the word “puppies” and your browser will display web pages the search engine has found in the hundreds of billions that has logged in its search index. While the search index is massive, it contains only a fraction of what is on the web.

Far more, perhaps 95%, is unindexed and so invisible to standard browsers. Think of the web as having three layers: surface, deep and dark. Standard web browsers trawl the surface web, the pages that are most visible. Under the surface is the deep web: a mass of pages that are not indexed. These include pages held behind passwords – the kind found on the office intranet, for example, and pages no one links to, since Google and others build their search indexes by following links from one web page to another.

Buried in the deep web is the dark web, a bunch of sites with addresses that hide them from view. To access the dark web, you need special software such as Tor (The Onion Router), a tool originally created by the US navy for intelligence agents online. While the dark web has plenty of legitimate uses, not least to preserve the anonymity of journalists, activists and whistleblowers, a substantial portion is driven by criminal activity. Illicit marketplaces on the dark web trade everything from drugs, guns and counterfeit money to hackers, hitmen and child pornography.

|

| World wired web Photograph: TeleGeography/www.telegeography.com |

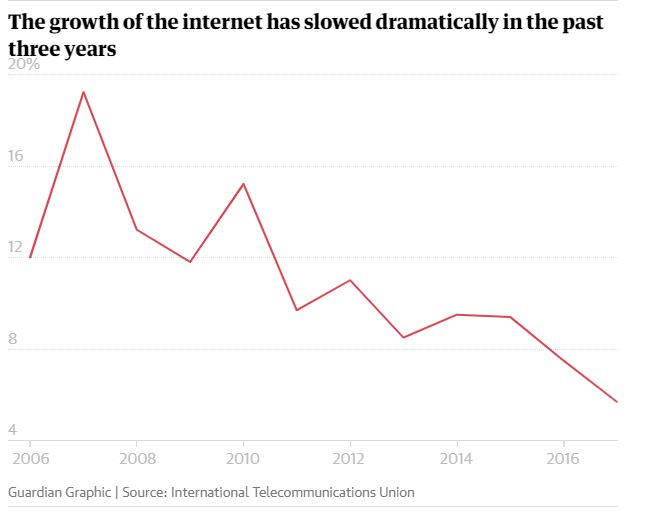

How many people are online?

It depends how you measure it. One metric popular with the International Telecommunications Union (ITU), a UN body, counts being online as having used the internet in the past three months.

It means people are not assumed to use the internet simply because they live in a town with an internet cable or near a wifi tower. By this yardstick, some 3.58 billion people, or 48% of the global population, were online by the end of 2017. The number should reach 3.8 billion, or 49.2%, by the end of 2018, with half of the world being online by May 2019.

Who are they?

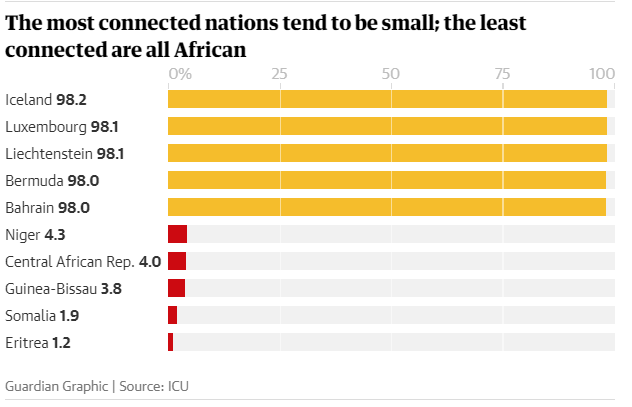

In some countries nearly everyone is online. More than 98% of Icelanders are on the internet, with similar percentages in Denmark, Norway, Luxembourg and Bahrain, the ITU says. In Britain about 95% are online, compared with 85% in Spain, 84% in Germany, 80% in France and only 64% in Italy.

Meanwhile, a 2018 report from the Pew Research Center found that 89% of Americans are online. The unconnected tend to be poorer, older, less educated and rural. The west does not dominate the online world, though. While the US has around 300 million internet users, China notched up more than 800 million in 2018, with 40% of its population still unconnected. India reached an estimated 500 million internet users this year, with 60% of the nation still offline.

What are they doing?

A minute on the internet looks like this: 156m emails, 29m messages, 1.5m Spotify songs, 4m Google searches, 2m minutes of Skype calls, 350,000 tweets, 243,000 photos posted on Facebook, 87,000 hours of Netflix, 65,000 pictures put on Instagram, 25,000 posts on Tumblr, 18,000 matches on Tinder, and 400 hours of video uploaded to YouTube.

Most consumer internet traffic is video: add up all the online video watched on websites, YouTube, Netflix and webcams and you have 77% of the world’s internet traffic, according to US tech firm Cisco.

|

What places are offline?

There is a stark divide between the haves and have-nots and poverty is an overwhelming factor. In the urban centres of some African nations, internet access is routine.

More than half of South Africans and Moroccans are online, and parts of other countries, such as Botswana, Cameroon and Gabon, are connecting fast. Mobile phones are driving growth thanks to mobile broadband costs falling 50% in the past three years.

But plenty of places are not keeping pace. In Tanzania, Uganda and Sudan, around 30 to 40% can get online. In Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone only 7 to 11% are online.

In Eritrea and Somalia, less than 2% have access. To build a mobile hotspot in a remote, off-grid village can cost three times the urban equivalent, which reaches far more people and so brings a much greater return on investment. In rural communities, there is often little demand for the internet because people do not see the point: the web does not serve their interests.

Are certain groups offline?

There is a clear age divide: far fewer older people use the internet than younger people. In Britain, where 99% of 16- to 34-year-olds are online, the 75-and-overs make up more than half of the 4.5 million adults who have never used the internet, according to the Office of National Statistics.

There is a serious gender gap too. In two-thirds of the world’s nations, men dominate internet usage. Globally, there are 12% fewer women online than men. While the digital gender gap has narrowed in most regions since 2013, it has widened in Africa. There, 25% fewer women than men use the internet, the ITU says.

Meanwhile, in Pakistan, men outnumber women online by nearly two-to-one, while in India, 70% of internet users are men. The divide largely reflects patriarchal traditions and the inequalities they instil.

Some countries buck the trend, notably Jamaica, where more women than men are online. This may be because more women than men enrol at the University of the West Indies in Kingston. The country has the highest proportion of female managers in the world.

How will the whole world get online?

A major challenge is to get affordable internet to poor, rural regions. With an eye on expanding markets, US tech firms hope to make inroads. Google’s parent company, Alphabet, scrapped plans for solar powered drones and is now focusing on high-altitude balloons to provide the internet from the edge of space. Elon Musk’s SpaceX and a company called OneWeb have their own plans to bring internet access to everyone in the world via constellations of microsatellites.

Facebook, which saw its Free Basics service banned under India’s net neutrality laws, has also abandoned plans for internet-beaming drones and is now working with local companies to provide affordable mobile services.

Microsoft, meanwhile, is using TV white spaces – the unused broadcast frequencies – for wireless broadband. Another approach, community networks, is also gaining ground. These mobile networks typically use solar-powered stations and are built by and for local communities. Run by cooperatives, they are cheaper than the alternatives and keep skills and profits in the area.

|

Is the internet good for us?

The bottomless pit of information we call the internet is a mixed blessing. As much as the internet spreads knowledge and understanding around the world, it also provides endless opportunities to waste time and develop unhealthy habits, such as obsessively checking social media. Research has linked excessive Facebook use with low self-esteem and poor life satisfaction, though cause and effect are hard to nail down. Twitter, which Amnesty International accuse of having created a toxic environment for women, asked for help in March in curbing trolls and misinformation. Meanwhile, doctors warn against taking tablets and mobile phones into the bedroom because of the sleep-disrupting impact of screens.

The ills of online life have forced some to turn their back on the internet, or at least the most time-draining, abusive, and addictive services. If Ofcom data is right, that could free up a whole lot of life. The watchdog found that the average Briton checks their mobile phone once every 12 seconds and spends a full 24 hours per week online, with some racking up a staggering 40 hours.

What next for the internet?

Many more devices, for one. The trend that started with mobile phones, tablets, MP3 players and TVs, has moved on to door locks, thermostats, light bulbs, coffee makers, fridges, dishwashers, ovens, washing machines, watches, toothbrushes, garden sprinklers, and, of course, home speakers. And there are more on the way.

The Internet of Things (IoT) will be a boon for firms that want to track our behaviour, and it may improve our lives in some respects, by handing us more control. But the IoT makes us more vulnerable to cyberattacks and breaches of personal data. In the first half of 2018, the cybersecurity firm, Kaspersky Lab, detected three times as many malware attacks on smart devices as in the whole of 2017.

Perhaps the most exciting internet buzzword today is decentralisation. Backed by luminaries such as Sir Tim Berners-Lee, the decentralised Web, or DWeb, aims to break down the walled gardens of the internet, where people experience the online world through operators such as Google, Facebook and others. Rather than a small number of firms holding masses of information on millions of people, the DWeb establishes a system whereby everyone holds and owns all their data, down to the level of individual likes on social media, and can choose precisely whether and how to share that information.

| Further reading Weaving the Web: The Original Design and Ultimate Destiny of the World Wide Web, Tim Berners-Lee The Future of the Internet and How to Stop It, by Jonathan Zittrain Googled: The End of the World As We Know It, Ken Auletta You Are Not a Gadget, Jaron Lanier Republic.com, Cass Sunstein This article contains affiliate links, which means we may earn a small commission if a reader clicks through and makes a purchase. All our journalism is independent and is in no way influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative. The links are powered by Skimlinks. By clicking on an affiliate link, you accept that Skimlinks cookies will be set. More information. |